Read the Excerpt From Chaucer's the Canterbury Tales, and Then Complete the Sentences That Follow.

The Canterbury Tales (written c. 1388-1400 CE) is a medieval literary work by the poet Geoffrey Chaucer (50. c. 1343-1400 CE) comprised of 24 tales related to a number of literary genres and touching on subjects ranging from fate to God'southward will to love, wedlock, pride, and decease. After the opening introduction (known as The General Prologue), each tale is told by i of the characters (eventually 32 in all) who are on pilgrimage to the shrine of Thomas Becket in Canterbury.

In The General Prologue, the characters concur to tell two stories going to Canterbury and ii coming dorsum to the Tabard Inn at Southwark where they started from, totaling 120 tales. If this was Chaucer'southward original plan and he never intended to deviate from information technology, then the slice must be considered unfinished at only 24 tales. Some scholars claim, however, that Chaucer did end the work, based on the tone and subject matter of the last tale and The Retraction appended to the manuscript.

The Canterbury Tales was popular centuries before it was actually published in c. 1476 CE. There are more copies of this manuscript than whatsoever other full-length medieval work except the penitential poem The Prick of Conscience, as well from the 14th century CE, which was only and then frequently copied due to its use by the Church. The Canterbury Tales is considered Chaucer'due south masterpiece and is amid the nigh important works of medieval literature for many reasons besides its poetic power and entertainment value, notably its depiction of the dissimilar social classes of the 14th century CE as well as clothing worn, pastimes enjoyed, and linguistic communication/expressions used. The piece of work is so detailed and the characters so vividly rendered that many scholars contend information technology was based on an actual pilgrimage Chaucer took c. 1387 CE. This seems unlikely, however, equally Chaucer held a total-time position from the male monarch at that time and any travels would have been noted in court records.

Chaucer's Life & Career

Geoffrey Chaucer was the son of a wealthy wine merchant of London, given a good education at local schools, and entered into service of the royal courtroom around the age of xiii in 1356 CE. He served under three English kings, Rex Edward III (r. 1327-1377 CE), Richard Ii (r. 1377-1399 CE), and Henry IV (too known as Henry Bolingbroke, r. 1399-1413 CE) in positions ranging from page to soldier, courier, valet and esquire, controller of the customs house of the London port, fellow member of parliament, and court clerk and poet, among other duties.

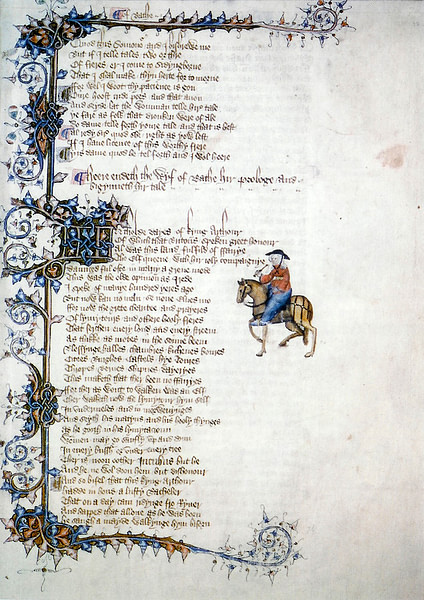

Portrait of Geoffrey Chaucer

Chaucer'due south works were never technically published during his lifetime equally that concept had not nevertheless been invented only he was well known and highly regarded as a poet equally his works were copied by other scribes who then shared or sold them. The events of his life are well documented in court records, and information technology is known he was recognized for his poetic achievements by Edward Iii (who granted him a gallon of vino daily for life for what was most likely a poetic composition) and rewarded financially by John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (fifty. 1340-1399 CE) for composing his first major work, The Book of the Duchess (c. 1370 CE) in honor of John of Gaunt's tardily wife Blanche.

Past the time Chaucer began composing The Canterbury Tales, he was at the superlative of his poetic powers and had traveled and read widely. He was fluent in Latin, French, and Italian, but wrote in the colloquial of Middle English language. The characters who appear in The Canterbury Tales are drawn from Chaucer's life experiences and are probably amalgams of people he had known (though some, similar Harry Bailey the Innkeeper, are historical individuals) and Chaucer'due south use of Middle English to tell their stories is especially constructive since he is able to return their various accents and dialects as they would have sounded at the time.

Characters

Chaucer, appearing as 1 of the characters in the story, describes the others when he meets them at the Tabard Inn at Southwark. The majority of the characters will tell a tale to the others as they ride toward Canterbury. These are, in the guild they appear in The General Prologue:

- Chaucer-the-pilgrim who narrates the piece of work; tells the 17th and 18th tales

- The Knight – a homo of honor, truth, and knightly; tells the 1st tale

- The Squire - the knight'southward son, a gentle youth of poetic sensibilities; tells the 11th tale

- The Yeoman – the knight'due south servant; no tale

- The Prioress (Madame Eglentyne) – a nun who supervises a priory; tells the 15th tale

- The Second Nun – secretarial assistant to the Prioress; tells the 21st tale

- The Nun's Priest – one of three priests traveling with the Prioress; tells the 20th tale

- The Monk – a worldly lover of hunting, riding, and drinking; tells the 18th tale

- The Friar (Huberd) – a corrupt clergyman who keeps donations for himself; tells the 7th tale

- The Merchant – a somber man who distrusts women; tells the 10th tale

- The Clerk – a scholar from Oxford University; tells the 9th tale

- The Sergeant of the Law (Homo of Law) – a wealthy lawyer; tells the 5th tale

- The Franklin (landowner) – a glutton, companion of Human being of Police; tells the 12th tale

- The V Tradesmen: Haberdasher, Carpenter, Weaver, Dyer, and Tapestry Weaver, all traveling together; described in General Prologue just no speaking parts

- The Melt (Roger) – works for the above tradesmen, loves to drink; tells fourth tale

- The Shipman – a ship's captain; tells 14th tale

- The Md of Physic (physician) – a greedy astrologer; tells 13th tale

- The Wife of Bath (Alisoun) – a widow who has survived 5 husbands and traveled the globe; tells 6th tale

- The Parson – a devout and honest chaplain; tells the 24th (last) tale

- The Plowman – the Parson's brother, devout and charitable; no speaking part

- The Miller (Robyn) – fibroid, rough, and fond of drinking and stealing; tells the 2d tale

- The Manciple (caterer) – purchases food for establishments; tells the 23rd tale

- The Reve (Osewald) – manager of an estate, an accountant; tells the third tale

- The Summoner – server of summons to ecclesiastical courts; tells the 8th tale

- The Pardoner – seller of indulgences (pardons) and simulated holy relics, rides with the Summoner; tells the 14th tale

- The Host (Harry Bailey) – Innkeeper at the Tabard where the pilgrims begin their journeying, proposes the story-telling contest and moderates/settles disputes

- The Canon's Yeoman – not introduced in the General Prologue; meets the pilgrims along the style; tells 22nd tale

Brief Summary & Best-Known Tales

The Canterbury Tales is narrated by a character whom scholars identify as Chaucer-the-pilgrim, a literary character based on the author but presented as far more naïve, clueless, and trusting than the actual Chaucer could have been. This aforementioned sort of narrator appears in Chaucer's before works, The Book of the Duchess, The House of Fame (c 1378-1380 CE), and The Parliament of Fowls (c. 1380-1382 CE).

Chaucer-equally-pilgrim takes the other characters at face up value and seems to admire them fifty-fifty when they are obviously very poor specimens of humanity. A reader understands the kinds of people this pilgrim is encountering through the skill of Chaucer-the-poet who reveals the characters through their oral communication, the type of story they cull to tell, interaction with other characters, and what they say of themselves, all highlighting their habits, interests, vices, and virtues.

Canterbury Tales

The poem opens with a grand description of springtime and nature stirring to life after the wintertime. This renewal inspires people to go on pilgrimage to the shrine of Thomas Becket, aka St. Thomas Beckett at Canterbury, i of the virtually popular pilgrimages in medieval Britain. Chaucer-every bit-pilgrim is at the Tabard Inn at Southwark, about to set out solitary on this pilgrimage, when the others arrive to spend the nighttime. He talks to them all at the communal dinner, and they invite him to travel with them. Their host, Harry Bailey, suggests they pass the time on the road with a story-telling contest. Each pilgrim will tell two stories on the way to Canterbury and two on the return; whoever tells the best story will win a gratuitous meal.

The next morning, they all fix off and the knight is chosen to speak kickoff. The other pilgrims are either chosen by Harry Bailey (referred to as The Host) or insist on speaking adjacent and interrupt whoever was chosen. Chaucer-the-poet gives Chaucer-the-pilgrim two of the worst tales and also makes fun of himself in the Prologue to the Human being of Law'south Tale in which he has the character mutter that every tale he tin can think of has already been told, however poorly, by Chaucer.

The Miller's Tale is one of the bawdiest in the collection but is amid those most ofttimes anthologized due to the brilliance of the plot & its seamless execution.

Among the all-time-known tales are the Miller's, the Nun's Priest's, and the Wife of Bath's although many of the others are of equal quality. The Miller's Tale is a fabliau, a form of French literature usually bawdy, satiric, and misogynistic in that wives especially, and women in general, are depicted every bit lusty, unfaithful, and stray. The French fabliau is amidst the genres the writer Christine de Pizan (l. 1364-c. 1430 CE) objected to in her work, and she would have no doubt extended this criticism to The Miller's Tale if she had known of it. This story is one of the bawdiest in the drove merely is among those well-nigh often anthologized due to the luminescence of the plot and its seamless execution.

The Miller tells his tale in response to the knight's tale of romance, love, chivalry, and the ways of fortune. The Miller'southward Tale features the dim-witted John the Carpenter, his young wife Alisoun, the scholar Nicholas who rents a room from them, and the parish clerk Absolon. Nicholas and Alisoun are frustrated considering they accept no opportunity to complete their matter since John is always effectually so Nicholas convinces John that a second Groovy Flood is coming soon and the only style to prepare for it is to suspend three wooden tubs by ropes from the ceiling of the house which they will each sleep in every night; when the Flood comes, they will bladder easily to safety. John installs the tubs and, when it is time for bed, all iii climb into their respective tubs, John goes to sleep, and Nicholas and Alisoun go back downstairs and to bed.

At this aforementioned time, Absolon has been pining for Alisoun and has gotten her to agree to giving him a kiss, simply when he raises his face to the chamber window, Alisoun sticks her behind out and he kisses that. Nicholas and Alisoun laugh at Absolon who runs off to get a hot poker for revenge. He returns and asks for another buss, and this time Nicholas puts his behind out the window, farts in Absolon's face up, and Absolon jabs him with the poker. Nicholas screams for water as he races through the house, and this wakes John who thinks the Flood is upon him, cuts the ropes, and plunges to the flooring, shattering his tub and breaking his arm. The neighbors hear all the commotion and come running to help but, after hearing the story, they dismiss John as crazy.

The Nun's Priest's Tale is a fable on the dangers of pride and flattery gear up in a farmyard. The proud rooster Chauntecleer has a dream that his life will be threatened past the fox, Daun Russel. He tells the dream to his wife, Pertelote, who dismisses it and tells him to go about his business as he ever has or else he will lose the respect of the hens in the yard who so admire him. One solar day, Chauntecleer is out for a walk and Daun Russel comes past and flatters him, asking if he volition sing him a song in his cute voice. Chauntecleer closes his eyes, stretches out his cervix, and opens his beak to crow when the fox snatches him upwardly in his jaws and runs into the woods. The whole undiscriminating follows in pursuit and Chauntecleer suggests to Daun Russel that perhaps he would like to pause to tell them their hope is lost and they should get back. When the pull a fast one on follows this suggestion and opens his mouth, the rooster flies up onto a tree branch and escapes.

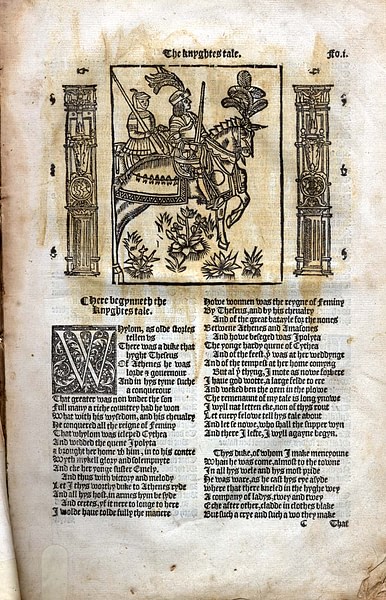

Illustration of The Knight's Tale past Geoffrey Chaucer

The Wife of Bath is the all-time-known character from The Canterbury Tales and her prologue is meliorate known and most often cited than her tale. She has traveled all over the globe, has had five husbands, and recognizes that God has given anybody something they are best at and, for her, information technology is sexual activity. She talks about each of her husbands and about her travels, ignoring or dismissing the complaints of some of the pilgrims who want her to get on with her tale, and makes information technology a point to highlight how she was the master in each of her marriages.

Her tale then picks up on his theme as she relates the story of a knight of King Arthur's court who rapes a maiden and is sentenced to expiry. Queen Guinevere intervenes and tells the knight he will be pardoned if, in a yr, he can return and tell her and her ladies what it is that women want most of all. The knight accepts these terms and leaves, spending the next year asking women what they want the most, but all the answers are subjective (money, honor, overnice dresses, freedom). He is on his way back to court when he meets an sometime adult female who says she knows the answer to his quest and will tell him if he promises to grant her a favor, which he does. Back at court, the knight tells the queen and her ladies the respond: what women want well-nigh is mastery over their husbands. Guinevere and her court concord and the knight is freed.

The pilgrims take their turn telling stories, argue, & interrupt until the Parson tells the last tale only as the sun is setting.

The old woman then requests her favor: she and the knight are to be married instantly. The service is performed, and the couple goes to their new abode. That nighttime, the woman asks the knight which he would prefer, that she remain old and ugly but exist faithful or become young and beautiful but cause him always to doubt her loyalty. The knight answers that whichever choice pleases her most is fine with him, and the lady, satisfied that she has mastered her husband, becomes the young and cute bride but promises to also be true-blue.

The pilgrims have their turn telling stories, fence, and interrupt, some so drunk they cannot speak or fall off their horse, until the Parson tells the terminal tale just as the sun is setting. His speech is not a tale but a dissertation on the Seven Mortiferous Sins and the value of a penitent heart. He points out that human being beings the world over are all pilgrims, traveling between nascency and death and going on to the afterlife. While he speaks, the sun goes down, and the party approaches a town for the dark. The work then ends with The Retraction in which Chaucer repents for all his major works, including The Canterbury Tales, and hopes God will forgive him.

Determination

The final tale and the retraction take led some scholars to conclude that The Canterbury Tales is a finished work. Scholar Larry D. Benson, for instance, writes:

The Retraction leaves u.s.a. in no incertitude that, unfinished, unpolished, and incomplete every bit The Canterbury Tales may exist, Chaucer is finished with it. One wonders if a more finished, more well-nigh perfect version could have been any more satisfying. (22)

At that place is no consensus, however, on what The Retraction means or whether information technology was fifty-fifty intended to exist included in the manuscript of The Canterbury Tales. No version of the work exists in Chaucer's own hand, all extant versions are copies and copies of copies, in which scribal errors modify who tells a tale, the tales appear in unlike society, or some do not announced at all. The most complete copy, The Ellesmere Manuscript (15th century CE) is the one most commonly used for modern-day editions of the work and includes The Retraction (as do many others) and so most scholars hold The Retraction was role of the original manuscript. Still, scholars who believe the work was left unfinished at Chaucer's expiry cite the plan outlined in The General Prologue and the non-speaking characters (such as the Plowman) who should take been given a tale as proof Chaucer never completed the work.

Whatever its country of completion, The Canterbury Tales has been entertaining and fascinating audiences since it was written. More whatever of Chaucer's other works, the Tales validated the utilise of Centre English language in vernacular writing as information technology brought the characters and their stories to life. Popular fiction of the Centre Ages was written in French poesy before Chaucer elevated Middle English poesy to the same peak of popularity.

His characters became as real to readers equally their family, friends, and neighbors, and the work was copied over again and again long before information technology was published in c. 1476 CE. Although his earlier works had earned him fame and the respect of his fellow poets and members of the court, The Canterbury Tales would make Chaucer immortal as the author of 1 of the greatest works in English and grant him the honorable epithet of Begetter of English Literature.

This article has been reviewed for accuracy, reliability and adherence to academic standards prior to publication.

Source: https://www.worldhistory.org/Canterbury_Tales/

0 Response to "Read the Excerpt From Chaucer's the Canterbury Tales, and Then Complete the Sentences That Follow."

Post a Comment